Oil & Gas Fundamentals

A oil & natural gas production information resource

RESERVOIR ROCK

Imagine standing on the shore of an ancient sea, millions of years ago. A small distance from the shore, perhaps a dinosaur crashes through a jungle of leafy tree ferns, while in the air, flying reptiles dive and soar after giant dragonflies. In contrast to the hustle and bustle on land and in the air, the surface of the sea appears very quiet. Yet, the quiet surface condition is deceptive. A look below the surface reveals that life and death occur constantly in the blue depths of the sea. Countless millions of tiny microscopic organisms eat, are eaten and die. As they die, their small remains fall as a constant rain of organic matter that accumulates in enormous quantities on the sea floor. There, the remains are mixed in with the ooze and sand that form the ocean bottom.

As the countless millennia march inexorably by, layer upon layer of sediments build up. Those buried the deepest undergo a transition; they are transformed into rock. Also, another transition occurs: changed by heat, by the tremendous weight and pressure of the overlying sediments, and by forces that even today are not fully understood, the organic material in the rock becomes petroleum. But the story is not over.

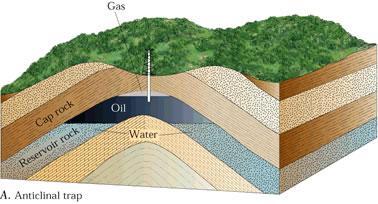

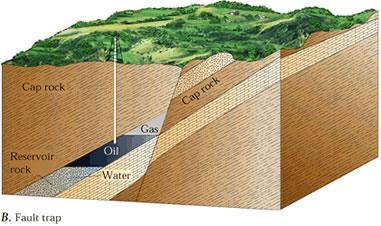

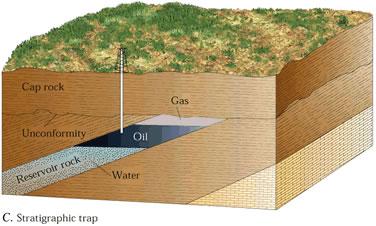

For, while petroleum was being formed, cataclysmic events were occurring elsewhere. Great earthquakes opened huge cracks, or faults, in the earth’s crust. Layers of rock were folded upward and downward. Molten rock thrust its way upward, displacing surrounding solid beds into a variety of shapes. Vast blocks of earth were shoved upward, dropped downward or moved laterally. Some formations were exposed to wind and water erosion and then once again buried. Gulfs and inlets were surrounded by land, and the resulting inland seas were left to evaporate in the relentless sun. Earth’s very shape had been changed.

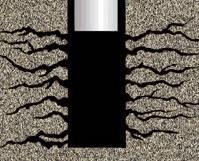

Meanwhile, the newly born hydrocarbons lay cradled in their source rocks. But as the great weight of the overlying rocks and sediments pushed downward, the petroleum was forced out of its birthplace. It began to migrate. Seeping through cracks and fissures, oozing through minute connections between the rock grains, petroleum began a journey upward. Indeed, some of it eventually reached the surface where it collected in large pools of tar, there to lie in wait for unsuspecting beasts to stumble into its sticky trap. However, some petroleum did not reach the surface. Instead, its upward migration was stopped by an impervious or impermeable layer of rock. It lay trapped far beneath the surface. It is this petroleum that today’s oilmen seek.

Petroleum Traps

SECURING LEASES

Drilling

Drilling To Total Depth

EVALUATING FORMATIONS

Examining Cuttings

Well Logging

Coring

COMPLEATING THE WELL

Production Casing

Cementing

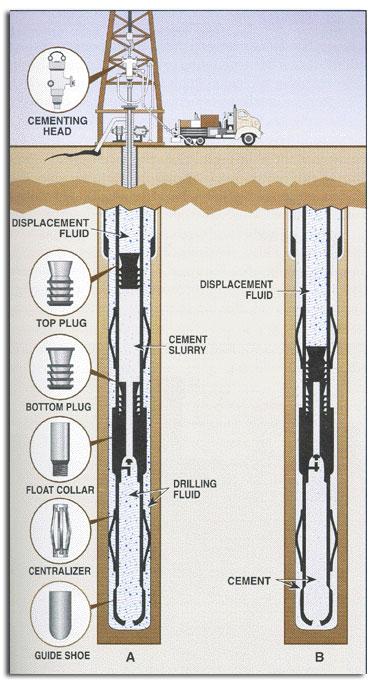

Special pumps pick up the cement slurry and send it up to a valve called a cementing head (also called a plug container) mounted on the topmost joint of casing that is hanging in the mast or derrick a little above the rig floor. Just before the cement slurry arrives, a rubber plug (called the bottom plug) is released from the cementing head and precedes the slurry down the inside of the casing.

The bottom plug stops or “seats” in the float collar, but continued pressure from the cement pumps open a passageway through the bottom plug. Thus, the cement slurry passes through the bottom plug and continues on down the casing. The slurry then flows out through the opening in the guide shoe and starts up the annular space between the outside of the casing and wall of the hole. Pumping continues and the cement slurry fills the annular space.

Cementing

After the cement hardens, tests may be run to ensure a good cement job, for cement is very important. Cement supports the casing, so the cement should completely surround the casing; this is where centralizers on the casing help. If the casing is centered in the hole, a cement sheath should completely envelop the casing.

Cement also seals off formations to prevent fluids from one formation migrating up or down the hole and polluting the fluids in another. For example, cement can protect a freshwater formation (that perhaps a nearby town is using as its drinking water supply) from saltwater contamination. Further, cement protects the casing from the corrosive effects that formation fluids (as salt water) may have on it.

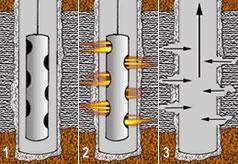

Perforating

Acidizing

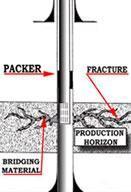

Fracturing

ARTIFICIAL LIFT

Sucker-Rod Pumps

Injection Wells

OIL PRODUCTION

Secondary Recovery

Operation

When all equipment is in place, the oil may begin to flow into the holding tanks to await pick up. It can be expected that a well will not be in production for certain times due to adverse weather conditions, mechanical malfunctions and other unforeseen circumstances. After the production period commences, it is necessary to incur certain costs in order to bring the oil to the surface. These costs include normal maintenance on the pump and other equipment, replacement of any pipe or tanks as needed, compensation to the operator of the pump, and payment of any incidental damages to the owner of the surface rights of the leased property. In some cases, the oil in a pay zone will be mixed with salt water. In such cases, the oil must be separated from the salt water and the salt water disposed of in a manner which is not harmful to the environment.

The water may be hauled away by tank truck but often this phenomenon requires the drilling, nearby the oil producing well, of another well into which the salt water will be pumped. The cost of this water disposal well is normally considered to be a cost of operation. Finally, there may be additional costs incurred in opening up a new pay zone when any presently producing pay zone becomes economically unfeasible. Because opening a new pay zone involves the installation of very little, if any, new equipment, the costs involved therein usually are not very substantial.

Sale of oil

These sale contracts are normally entered into for periods of not longer than a few months but in no case longer than one year. The buyer of the oil will generally be advised by the operator of the working interest as to the identity and extent of ownership of each of the holders of the working interest, as well as the identity of the royalty holders and the amount of their interests. The information will be compiled on division orders which are the basis upon which the buyer of the oil can divide the proceeds of sale among the various holders.